Some years ago, Laura Jones (RSS Class of ’72) was washing dishes while visiting family members. A recording of railroad songs was playing in the kitchen. Unexpectedly, in unison with The Ballad of Casey Jones, she began to sing along, and knew all the verses! She even had a repertoire of movements synched with the words:

“Stick your head out the window, see the drivers roll,” etc. Astonished family members said it looked like something out of vaudeville;

“Where did you learn that?” they asked; and

“Why, don’t you remember? In Grade 4—in Miss Burn’s class.”

It amazes me, such nonsense that we all can recall from childhood. But some of it is still relevant, and I believe the late Eva Burn still influences more of us today than many other teachers. What makes her special? I doubt we recognized it at that time—we were disrespectfully making fun of her appearance, or her spinsterhood, because we perceived such qualities as eccentric.

So consider this: it’s possible we’re all better off for her own lack of children. She thus poured her enthusiasm and knowledge into us, her students. She had much more time to explore the world as a result, and the natural world benefitted. She was an amateur naturalist in a region not well documented at that time, and became the go-to person for anyone finding some curiosity. I remember her showing an enormous live Cecropia moth in class. Her theory was that it came as a cocoon on a railroad car from the USA, and hatched in the Revelstoke yards. Show an impressionable kid things like that, and they don’t forget.

Do you remember the wildflower collections she had us make? We all had presses for drying them, and had to be careful not just to rip off a stalk, but to collect the entire plant, and then press it in such a way its blossoms could later be examined for distinguishing detail. There was a prize for the pupil with the most species, and another for finding the most blossoms on a single tiger lily stem. I knew I was running third in the ‘most plants’ category, but made a valiant last-day effort to win the wild lily prize. I cringe now for the plants I wasted in that effort. Every time I pulled a better one, a previous specimen would be discarded—never to grow again—all within the boundary of the National Park!

I also recall a so-called “sensitive plant” in her classroom. Thirty years later, I was wandering with a friend in the tropical jungles of Queensland, Australia. Walking down a red dirt road, I espied a low plant growing in the ditch. It had foliage which looked like miniature mountain ash leaves—you know, with tiny leaflets along a central stem? Such a leaf was vaguely familiar because I recalled one of Miss Burn’s fantastic potted plants. If you touched it, the leaves would fold like a fan to protect themselves from harm. This wasn’t a slow closing like the evensong of a Prayer plant. Its sudden response was such a magical thing that I remembered it for decades, and had been touching all sorts of plants since, in hope of reigniting my delight. I’d fondled exotic plants in botanical gardens, acacia trees in Hawaii—anything which looked similar, because I didn’t know how big the plant grew in nature. So I descended into the ditch and poked it. IT COLLAPSED! I shouted to my companion, who hurried over to see what wonder awaited. This attracted other walkers, who clustered about. All but me were greatly disappointed. Did they expect to find me wrestling some poisonous snake? I don’t know, but I had just re-discovered Mimosa pudica after decades of fond memory and searching. That wondrous potted sensitive plant in Miss Burn’s Grade 4 class was but a common weed in the southern hemisphere!

Eva Burn came to love the outdoors as a child on a self-sufficient farm at Montana Slough, just south of the airport. With this interest she also became a great mountain hiker and believed one could only observe nature properly on foot. She also skied until the age of 75, and swam in Williamson’s Lake for 70 years.

Following high school, she attended what was called Normal School in Victoria for two years, where she learned teaching technique. She started teaching classes two weeks before turning 18, and was employed continuously thereafter in schools at Sicamous and at Revelstoke. She retired in 1975, having put 47 years before the blackboard.

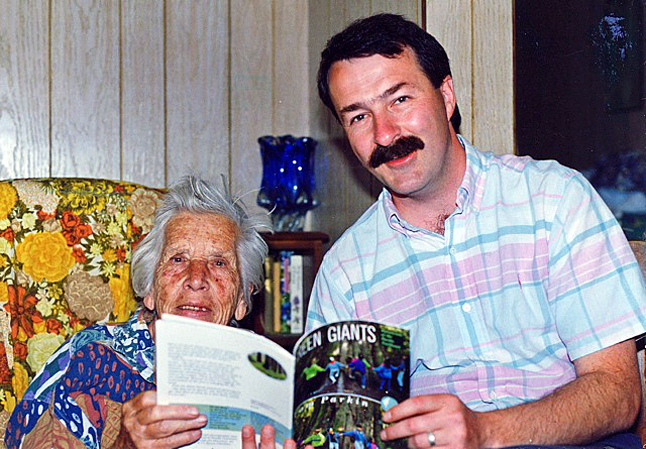

I visited her in 1992, while travelling through Revelstoke on a book tour. She welcomed me into her home at 802 1st Street West, where she spent 65 years. It had been over 30 years since we last met, but she declared that she remembered me; an amazing possibility. My purpose was to express appreciation for her having inspired in me a lifelong interest in natural history, which in turn started my own career in the national and provincial parks. I brought proof—a children’s book I’d written about the temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest. A reporter from our dreaded competition, the Revelstoke Review, came to document the meeting, which was all the honour I could think to pay the old dear. We passed some hours of enjoyable conversation, and she was particularly proud to mention other of her students who had become biologists or accomplished in the sciences.

In whatever you have accomplished in life, likely there was a teacher who recognized and encouraged in you the germination of a seed of interest or talent. Our teachers are oft forgotten in life’s strivings; and yet they moulded, if not made us. Sometimes we think we did it all ourselves. Yes, it’s a paid role for them, but some touched us with their spirit or their dedication. Eva Burn did that for me. Before it’s too late, consider your own un-thanked mentors and make contact to tell them that they made a difference.