By David F. Rooney

It should come as no surprise to anyone that the Trans-Canada Highway and the CP Rail line are major and often fatal obstacles for wildlife. But are they barriers to procreation?

That’s a question biologist Kelsey Furk hopes her research can answer as it pertains to one of Canada’s most elusive mammals — the wolverine.

“They’re a hot topic of research these days,” she said in an interview on Wednesday.

“We’re looking at DNA analysis and relatedness to see if they are crossing the highway.”

Furk and fellow biologist Lisa Larsen use a number of bait stations at different locations in Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks. Each station consists of a tree wrapped in barbed wire that is then coated in lure that attracts any wolverine that smells it. When the animal climbs the tree to investigate the barbs snag a hair sample for DNA analysis. Trail cameras posted nearby confirm the presence of wolverines at the site and records their behaviour. (Click here to watch the antics of one wolverine.)

Furk believes that her research may demonstrate that these barriers — in particular the Trans-Canada, which carries more than 4 million vehicles a year — are more than just major and often fatal obstacles for wildlife. These wolverines that call our local national parks home may slowly be dying out as the highway proves to be a barrier to their procreation.

“Our samples will be added to a pool of samples that have been collected regionally and that will enable us to see how they’re impacted by habitat fragmentation,” she said.

Her research may also give scientists a clearer idea of how many wolverines live here. Research from a study in the 1990s indicated the population in the Northern Selkirk Mountains to be approximately one wolverine for every 167 km2. Of this area, Glacier is 1,349 km2 and Mount Revelstoke is 260 km2. (Click here for more relevant wolverine facts.)

Wolverines in western Canada, including the Mountain Parks, have been recommended as a Species of Special Concern by the national Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). This ranking reflects their low numbers and slow capacity to recover from

Research indicates that wolverines that spend the majority of their time in protected areas have a higher survival rate. But at least two hit and killed in the 1990s by vehicles in the last few years. Unlike Banff National Park where overpasses were built specifically to assist wolves, bears, cougars, lynx and wolverines, no mitigation measures are in place for wildlife other than signs warning of animal crossings. Both Alberta and British Columbia provincial governments recognize wolverine as a species that may be at risk and require special management considerations.

Furk said visitors and local residents can provide valuable assistance to her study by notifying her if they happen to spot a wolverine.

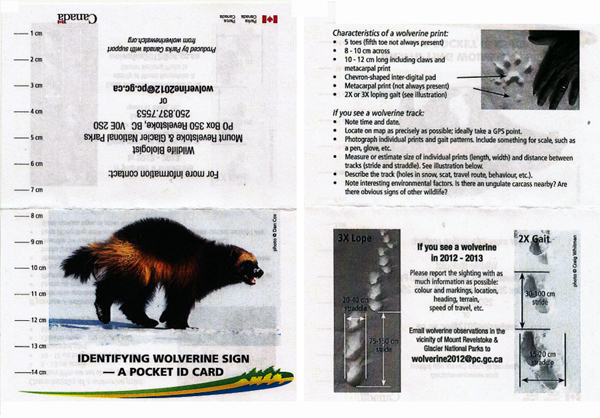

Pocket ID cards have been developed that can help you identify an animal or its tracks. They are available at the Parks Canada office next to the post office.

Wolverines can be about the size of medium-sized dogs, they have brown and gold fur with pale markings on their faces and chests. They look like a very small bear, albeit with a noticeable tail.

“You’re pretty lucky if you get to see a wolverine,” Furk said. But despite their reputation as elusive and ferocious carnivores people do see them.

For instance I saw one in May at the turnoff to the Mount Revelstoke chalet during the Chickadee Festival several years ago. One was spotted this year by member of the Parks staff.

To discover more about wolverines please contact the wildlife biologist at 250-837-7553 or e-mail wolverine2012@pc.gc.ca.