Current Publisher and Editor

One hundred years ago today, Monday August 4, Canadians flocked to recruitment offices across the country to enlist in the army or navy to fight in the First World War.

For the most part they were patriotic young men who wanted to do their part to defend the Empire against the Germans. My grandfather was one of them. It’s only recently that I uncovered his part in the war to end all wars.

The willingness of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers — 620,000 of them by the end of the war — to offer themselves up for national service is described in other media outlets this weekend, notably this article in The Globe & Mail — The Eager Doomed: the Story of Canada’s Original WWI Recruits and I have no intention of discussing that further.

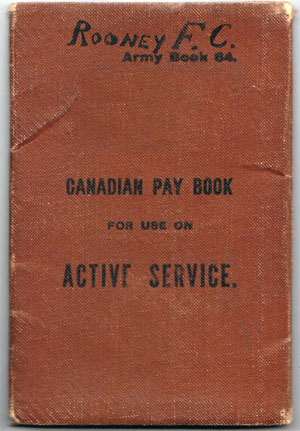

But this anniversary prompted me to look back at my own family history. My father did not often talk about his dad , Francis Carmody Rooney, other than that he had served in the army during the First World War. I knew, too, that he never made it to the trenches because of influenza epidemics that swept through the Canadian Army’s camps in the UK. Beyond that I knew nothing.

When my father’s only sister died a few years ago I received a smattering of old photographs and

other documents dating back to his time in the military. He died when I was only four years old so I have no recollection of him and never got to ask him anything. I knew he went into the insurance business after the war and was rather successful — enough so that the family didn’t suffer during the Great Depression — and that he was an avid amateur photographer. Using his Rolleiflex camera he chronicled family life through the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s and early to mid-1950s.

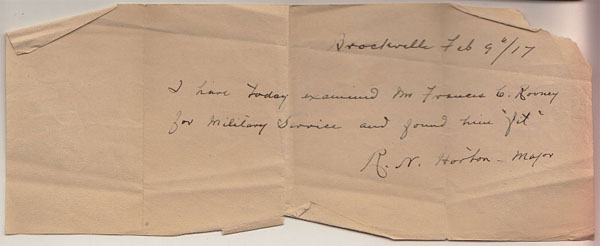

I can’t help but think that Frank, described by my mother as a very kind and gentle man, was at some level as excited by the prospect of war as every other young man in his hometown of Brockville, Ontario. He enlisted as a gunner in C Battery of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery and in those early photos he looks proud of his uniform.

He was medically examined and pronounced fit for active service in 1918 then shipped to England where he spent months in additional training. But he never made it to the trenches. Epidemics of measles (2,186 men hospitalized, and 30 deaths), German measles, aka Rubella accounted for 2,641 cases) and influenza swept through Canadian Expeditionary Force camps on both sides of the English Channel. Influenza was a significant killer during the war years and, late in the war, the 1918 flu pandemic was felt by all the deployed armies. There were 45,960 cases of influenza in the CEF and 776 fatalities. The great Spanish Influenza Pandemic began in 1918, sweeping through the armies on both sides of the great conflict, including Canadian Army camps in England. The disease eventually killed 20 million mostly young people around the world, including 50,000 Canadians.

For men like my grandfather it meant they never went to the front lines before the Armistice was declared on November 11, 1918. The war was over and you’d think that would be it; Canada’s men at arms would be sent back home. You’d be wrong to think that.

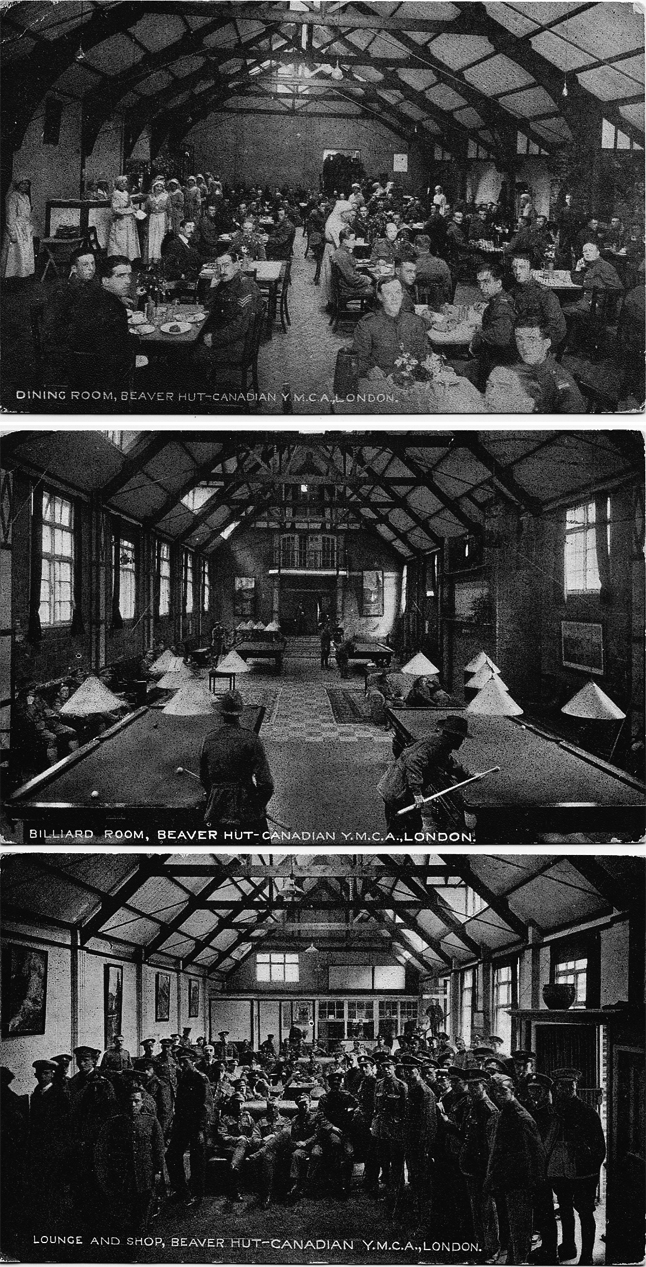

That’s not quite what happened. Thousands upon thousands of Canadian servicemen like my grandfather found themselves stranded in their camps in England awaiting passage on steamers that, with war’s end, were more interested in turning a profit than helping their country repatriate the army.

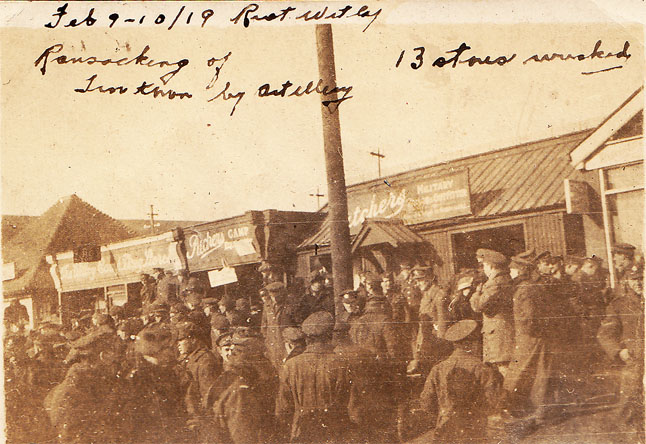

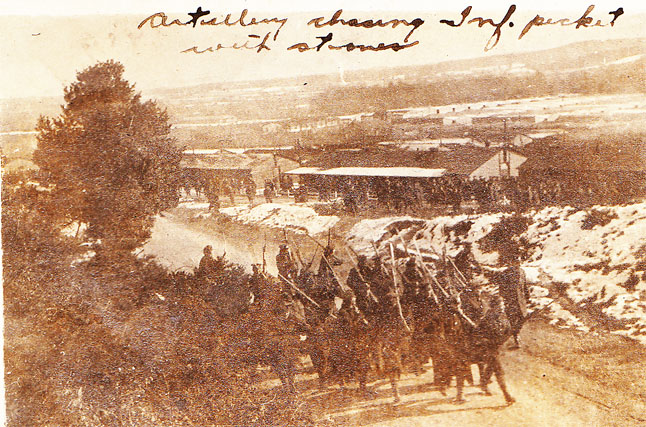

Bored and angry soldiers in several camps rioted. The same thing happened at Witley on February 9, 1919, after some soldiers where arrested by military police.

While I have hundreds of letters sent between my maternal grandparents between 1910 and 1920, I have only a few postcards and photos from my father’s dad.

This is what happened, according to the Open University’s International Centre for the History of Crime, Policing and Justice:

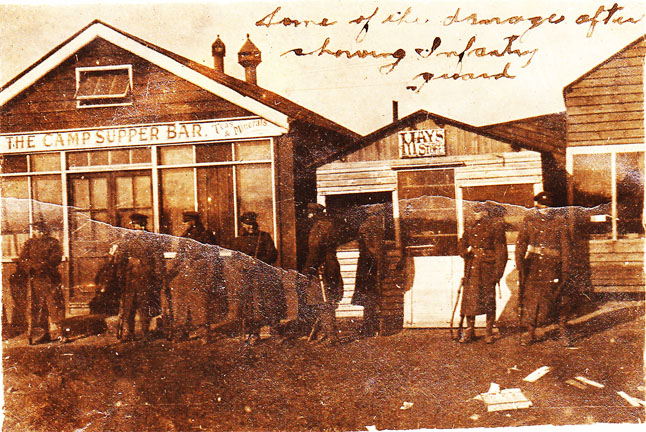

“There had been rioting on Armistice Day and a good many other incidents which as a rule were not very serious. Those arrested were rescued who then wrecked the officer’s quarters; the canteen was looted and all the drink stolen; then an attack was made on a number of shops known as ‘Tin Town.’”

My grandfather took some photos of the riot and its suppression by Canadian infantrymen with fixed bayonets and eventually was shipped back home to Ontario.

I am sure it is not what he expected when he donned a uniform, but I would guess his expectations didn’t match reality. Fortunately, unlike 67,000 other Canadians who were killed and 250,000 who were wounded, he made it back alive and unhurt. And for that I am grateful.

What did your grandfather or great-grandfather do during that long-ago conflict? Take a look! You might be surprised by what you discover. History, after all, touches us all in one way or another.

Here are my grandfather’s photos of what was undoubtedly one of the most significant incidents in his war experience: