By David F. Rooney

MICA — The iconic mountain caribou may be a step closer to a new lease of long-term survival through the Maternity Penning Project up river from Revelstoke near Mica.

Eight of the pregnant caribou cows captured on March 24 have given birth of healthy calves weighing between 6.5 and 10 kilograms each. The ninth is expected to drop her calf soon and all of the animals will be released back into the wild in mid-July.

The intention of the project, overseen by the Revelstoke Caribou Rearing in the Wild Society, is to try to pull the ungulates back from the brink of extirpation. Extirpation? Local extinction? Without some kind of human intervention, that’s a very real possibility.

These animals, a subset of the broader Southern Mountain Caribou population, are adapted to the deep snows of the Columbia Mountains and migrate up and down mountains in search of seasonally available food, which, in winter, consists exclusively of tree lichen. They are dependent on old forests for forage and to spatially separate themselves from other ungulates such as deer and moose.

Mountain Caribou are listed as a threatened species under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act. Populations began to decline dramatically around 2002 and continue to decline. Today, several herds are extremely small and without intervention may be extirpated in the near future.

The Columbia South herd (just south of Revelstoke) consisted of 120 in 1994 and approximately seven in 2011. The Columbia North herd (just north of Revelstoke) was about 210 in 1994 and was estimated at 120 in 2011.

These two populations have been extensively studied since the mid 1990s. Today scientists know a lot about caribou, including information on mortality, population trends, and habitat use. Current threats to caribou include habitat loss, small population effects, altered predator-prey dynamics and direct and indirect disturbance.

Pregnancy rates for mountain caribou are consistently high, however, the number of calves has declined and calf numbers are too low to sustain the population. Finding ways to increase calf-survival rates by capturing pregnant cows and keeping them safe until their calves can be safely released is a method that has been used in the Yukon and Alberta to increase improve the health of caribou herds.

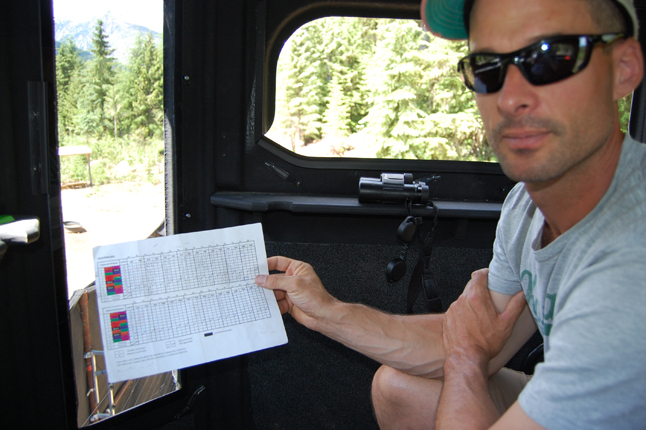

“You look at herds that consist of seven or eight animals — they’re unsustainable,” says forester Kevin Bollefer, a member of RCRW who, along with Cory Legebokow of the BC Ministry of the Environment, guided two journalists to the maternity pen erected north of Revelstoke. “What do we do with herds that small? Fold them into this one?”

Maybe. Maybe not. That’s a decision for another day. For now, though, the maternity pen is — so far — a major success.

Built last autumn and staffed with $500,000 in cash and kind from governments, corporations large and small, and many other companies and individuals (please click here to see a full list of the contributors), the pen is a surreal artifact constructed in the forest on the west bank of the Columbia River.

“One of the real neat things about this project is that… we have pulled together representatives from the entire community… who have all contributed to mountain caribou recovery in the past,” he said.

The different organizations haven’t all seem eye-to-eye in the past but they all see value in helping these beautiful animals survive.

“We’re all sitting down at the table,” Legebokow said.

The 300-metre x 200-metre patch of woodland, located about 100 yards behind Brian Glaicar’s Monashee Outfitters lodge, is fenced with black geocloth so the cows and their offspring are not visible to predators. As a further precaution it is surrounded by a six-foot-high electric fence. Trail cams monitor the perimeter and while photos have been taken of black bears, grizzlies, wolves, cougars and even a wolverine none have attempted to investigate the pen.

It’s hard to imagine, but, as Legebokow said, “Wait ’til you see the fence. Then you’ll understand.”

The fence is so alien to the landscape that it must be completely incomprehensible to the animals that wander past it, even though they must surely hear and perhaps even smell the caribou in the pen. Still, predators are smart creatures. When the Big Day came at another maternity pen, caribou shepherds — the men and women who keep a daily watch over the ungulates — who went to release their charges found a large black bear waiting by the gate.

Bollefer said nothing like that will happen here.

“We’ll sweep the area first and Brian has hunting dogs; maybe we can use them, too,” he said.

Looking into the pen from one of the observation posts on the perimeter shows that the underbrush it contains is much like that in the forest surrounding it. You can occasionally hear a cow grunting but unless they cross a small clearing they are difficult to spot.

Still, the animals know when their water and food troughs are filled and will approach to within 15 or 20 metres if humans are inside the pen. Once the humans are on the other side of the wall the four-legged mothers and their playful children come down to feed and drink.

So far, so good. The project looks like a major success. Somewhere down the road researchers will catch up with the animals and determine how many of the calves have survived.

Can they actually help ensure the survival of the mountain caribou in this area.

Bollefer believes the society has a solid chance at success. Unlike areas south of Revelstoke where the caribou have vanished, there is no agricultural development and little industrial development in the mountains north of town. That should help, but really it’s all in someone else’s hands.

“Mother Nature will ultimately dictate what’s going to happen,” he said.