By David F. Rooney

Some time in the next few years white-nose syndrome (WNS), a fungus-driven disease from Europe that has ravaged bat populations from New England to the the Canadian Maritimes, Quebec and Ontario as far west as the borderlands between Ontario and Manitoba is expected to reach western Canada.

While the disease has been seen in Europe for at least 30 years, it does not produce the same devastating effects seen across the Atlantic, perhaps because European bat species are heartier, have evolved resistance to the disease, or simply because the European strain of Geomyces destructans, as the fungus that causes WNS is formally known, is less aggressive than what is seen here.

Regardless, the ultimate outcome of WNS in North American bats is death on a massive scale as wing deterioration and loss of body mass makes it impossible for bats to survive a normal winter. The fungus produces a fuzzy white growth on the bat’s snout, wings, and ears, and sometimes penetrates into the bat’s hair follicles and sebaceous glands (oil producing), generating ulcers on the skin.

The latest American estimate suggests that WNS is responsible for the deaths of between 5.7 and 6.7 million bats in the eastern US. The Americans predict similar similar death scale in Canada.

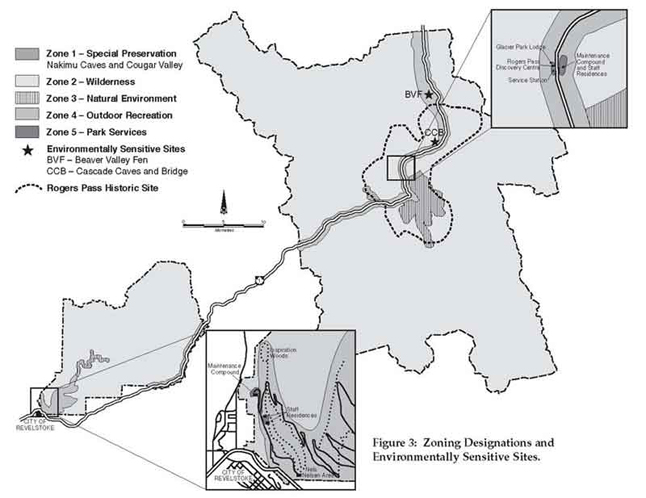

Parks Canada is eager to begin assaying bat populations in the mountain parks and is currently trying to assess whether the Nakimu cave system in Glacier National Park is home to a hibernating bat population.

“We simply don’t know,” Parks’ Communication Officer Jacolyn Daniluck said last week.

She said the COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) recommended that the Little Brown Bat and the Northern Bat be added to the endangered species list. Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks are home to nine bat species including those two species.

“Parks Canada understands that bats play an important role in the ecosystem as night-time pollinators and in pest control and are taking measures to protect them,” Daniluck said. “It is presently unknown if bats use the Nakimu Cave System. Results from the research will inform Parks Canada how to best manage the caves as they were one of the original tourist attractions of the area.”

She said Parks personnel, led by Parks ecologist Sarah Boyle and accompanied by local and out-of-town media reps, are to visit the cave system on Thursday, August 1. (The Current was invited to participate, however, my heart condition is such that I shouldn’t risk the helicopter ride and hike along a rough mountain trail to and from the cave, which is located at about 2,000 metres.) The Times Review is sending a reporter along and you should be able to read his report in next week’s print paper. Current readers will have to make do with photos from Parks Canada and interviews with Parks scientists.

Ken Kingdon, a biologist with Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba has been following the westward progress of this lethal fungus and told The Revelstoke Current that it hasn’t yet appeared in Manitoba’s bat population. However, that could change this winter as the inter-lake region north of Winnipeg has a large bat population. He said bats are known to move between the two provinces. But they could also reach Manitoba from North Dakota.

“The reality is that we don’t know much about our hibernating bats,” Ann Froschauer, National White-Nose Syndrome Communications Leader for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, wrote in her blog. “There are hundreds of thousands of caves and mines in North America, the majority of which have never been surveyed for bats. Unfortunately, in the East WNS moved so quickly we will never know exactly how many bats there were.”

“In consultation with Canadian partners, we estimated bat losses in affected provinces based on estimates from WNS-affected states and the assumption that bat densities in the affected region of Canadian provinces are comparable to those in bordering states. This assumption is based on summer capture data and knowledge of wintering populations and habitat.”

Since so little is known about bat populations, researchers across North America and Europe are scrambling to catch up. WNS has been seen in Europe for at least 30 years but for some reason mortality in rates in Europe are nothing like the 95-to-100 per cent mortality rates that have been seen in Eastern North America

It is unlikely that bat populations of North America undergoing extreme mortality due to WNS, can rely on a few survivors that might be able to adapt to this disease. Current rates of mortality among North American bats with WNS are unprecedented and seem to be outpacing the rate at which survivors might compensate, recover, reproduce, and persist.

The simulation below was generated by the University of Tennessee’s Kraken supercomputer to represent WNS’ spread across the continental United States. The simulation suggests it would slow somewhat once it hit the plains in 2014 then continue slowing down in 2015 until it reached Colorado. Then it would once again expand rapidly. (Click here to read an article about this.)

Manitoba and Saskatchewan are both worried about WNS and in Alberta last year the provincial government ordered the gating and closure of Cadomin Cave, a popular recreational cave near Jasper that houses about 800 hibernating bats each winter.

British Columbia has the most to lose of any province in Canada, as BC is home to 16 species of bats, the greatest bat diversity in Canada. Fourteen of these species are thought to hibernate, and would therefore be at risk of dying from WNS. Of the 16 species of bats in BC, half are red- or blue-listed and 13 have Conservation Data Center listings other than Secure. Once listed as a ‘Secure’ species throughout its range across North America, little brown bats are being hardest hit by WNS; in affected areas in the US northeast this once common species has been extirpated in many areas.

The provincial government here in BC issued an alert about WNS in 2001 (click here to view that document) and this year the Ministries of Mines, the Environment and Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations issued a decontamination order for sites where bats are present. (Click here to read that order)

WNS spores can be spread in mud on boots, dirt on equipment, as well as by infected bats. The longer it takes WNS to reach the mountains, the more time this buys researchers seeking viable mitigation strategies.