The 505-million-year-old Burgess Shale in Canada’s Yoho National Park is famed for its bizarre marine animal fossils, most of which are thought to be found nowhere else on the planet. A paper published today, July 31, in the prestigious British scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests that, in fact, one of its most famous animals had relatives spanning the globe.

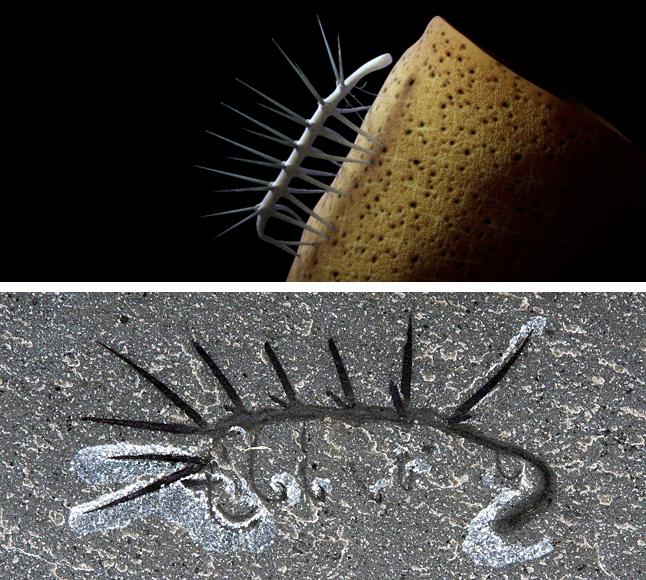

Hallucigenia sparsa is a spiny, worm-like animal with numerous pairs of soft walking legs. Originally described from the Burgess Shale over a century ago, this rare creature has long baffled scientists who struggled to better understand how it lived and if it had any relatives. Today’s study, lead by a team from the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), University of Toronto and the University of Cambridge, reveals that Hallucigenia had relatives all over the world.

A statement from Parks Canada said that upon re-examining Hallucigenia specimens using cutting edge techniques, researchers noticed that its defensive spines strongly resemble a group of small, isolated spiny elements found worldwide that had puzzled scientists for decades, with both groups of spines having subtle surface ornamentation and a structure resembling a stack of ice cream cones. These characteristics were sufficiently unequivocal for researchers to suggest that the small isolated spines were indeed related to Hallucigenia. Along with its relatives, Hallucigenia formed a group of animals that spanned the planet’s ancient Cambrian seafloors.

“From Canada to the United States, China to Mongolia, and the United Kingdom to Australia, we now know that during the Cambrian period Hallucigenia had relatives all over the world”, said Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology at the ROM and lead author of the study. “This study shows that because spines were more resistant to decay, they could actually preserve more readily in many conventional fossil deposits but it is only in exceptional sites like the Burgess Shale that we find complete articulated specimens with spines attached to the rest of these delicate soft-bodied animals.”

“The hard bits and pieces of animals found in conventional fossil deposits go hand-in-hand with the information provided by the Burgess Shale and similar ‘exceptional’ deposits – taken together, these data sources provide a unrivalled insight into the evolution and ecology of the earliest complex animals,” said the study’s co-author, Dr. Martin Smith from the University of Cambridge.

The study said Hallucigenia bears a striking resemblance to its modern relatives, the velvet worms, which live in fallen logs in jungles throughout the world – though Hallucigenia long preceded the earliest forests, or indeed the earliest life on land.

Caron said that despite this difference in habitats, the Cambrian forms were probably micropredators or scavengers like their modern counterparts and probably filled similar ecological roles.

Though it was discovered more than a century ago, Hallucigenia was first restudied by renowned palaeontologist Simon Conway Morris in 1977 because of its “bizarre and dream-like quality,” much like a hallucination, and has gone on to become one of the Burgess Shale’s most recognizable creatures.

Managed by Parks Canada in Yoho National Park, the Burgess Shale was recognized in 1981 as one of Canada’s first UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Now protected under the larger Rocky Mountain Parks UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Burgess Shale attracts thousands of visitors to Yoho National Park each year for guided hikes to the restricted fossil beds from July to September. Both Parks Canada and the Burgess Shale Geoscience Foundation lead hikes to the fossils. The bulk of Burgess Shale specimens are held in trust for Parks Canada at the ROM in Toronto.

To learn more about the Burgess Shale visit: www.burgess-shale.rom.on.ca