MARA — There is always a long queue at the Wild Flight Farm stand at the Revelstoke Farmer’s Market in summer and the Winter Market in winter. Loyal customers patiently wait, often with baskets or cloth bags in hand, as they pass bins of plump rutabagas, radishes and a few items they may never have heard of. In the summer, children can be seen on Grizzly Plaza eating organic watermelon radishes like candy and you know they came from the Wild Flight Farm stand.

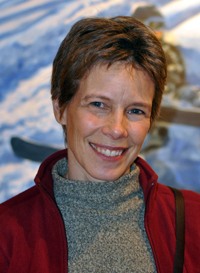

The Revelstoke Farmer’s Market and Revelstoke customers shaped the way the farm has evolved, said Hermann Bruns, who owns the farm at Mara (south-west of Sicamous) with his wife Louise. They run the farm with their 17-year-old son, Ari, 13-year-old daughter, Elena, and up to seven employees in the busy summer season.

Wild Flight farm’s summer produce was so popular that Hermann and Louise added a winter box program with stored vegetables. Some customers who didn’t subscribe to the box program wanted to be able to buy individual produce so they brought tables to the pick-up area and sold extra vegetables. Soon “we found we needed a bigger venue and other vendors wanted to join in,” Hermann explained, and that led to the creation of the biweekly Winter Market at the Community Center.

At first, Hermann and Louise were “fairly idealistic” and only sold their own vegetables or vegetables from around BC at their stand and in their winter boxes. But their customers wanted more variety than winter storage vegetables could provide. “To be fair, no one lives entirely on local produce,” Hermann said. Now the Bruns also sell organic vegetables from the United States and Mexico, in addition to other BC farms. The labeling on the bins indicates where the produce is from.

That makes the winter market different from the summer farmer’s market. “I think you need a different set of rules for winter farmers’ markets,” Hermann said. And because the Bruns started the winter market, they were able to set those rules. If someone joins the winter market and produces something that another vendor imports, the one who produces the item him- or herself will take precedence. “That way it doesn’t discourage other farms from developing their product list.”

Hermann and Louise bring a lot of pragmatism and a scientific approach to their organic farming business. Both are biologists by training. They met while working as environmental technicians at the coal mine in Tumbler Ridge. Hermann had grown up on his parents’ dairy farm at Mara and Louise came from Ottawa. Hermann knew he didn’t want to be in the dairy business and Louise had an interest in organic market gardening. They decided to return to Mara and start an organic farm. In 1992, they settled on 20 acres of land that now borders Hermann’s brother’s large dairy farm. They grow vegetables on about half their acreage and seed the rest with cover crops or ‘green manure’ to help rebuild fertility for planting vegetables there the following year.

The Bruns’ scientific training is evident in their approach to farming. When asked about common strategies suggested in organic farming literature, Hermann asks for evidence that they work. He doesn’t practice companion planting, for example, because he hasn’t seen persuasive evidence of its usefulness. “A lot of the claims are anecdotal,” he said.

Other unproven theories include putting out beer to catch slugs. Although slugs like to get into the lettuce there is no organic way to eliminate them, he said. Instead, the Bruns avoid planting whole heads of lettuce. They prefer to grow mixed lettuce leaves which can be cut off and are good for a second crop before they need to be replaced by fresh transplants.

Pests need to be controlled on a species by species basis. For example, the cabbage root maggot, which also affects the salad turnip, is controlled by a fly screen that prevents the fly from getting near the plant to lay its eggs.

Other gardening theories like square-foot gardening and permaculture are not suitable for market gardens. Square foot gardening promotes smaller, more manageable quantities of food and Hermann has “yet to see a working farm using permaculture. We have to make money,” he said.

The value of crop rotation is not a myth, but it is hard to manage when growing so many crops. “We don’t have an organized rotation,” Hermann said, rotation just happens.

In Revelstoke, many gardeners wait until the May long weekend to plant in an effort to avoid frost damage. Hermann argues that

planting can take place much earlier – in fact, at Mara (a slightly warmer location than Revelstoke), most planting occurs at the end of April. “Lots of things can be planted early,” he said. And planting should be continuous, not a one-off deal.

There are plenty of risks in farming. Bad weather or pests can destroy entire crops and “there can be weed issues,” but the Bruns do not have crop insurance. “We try to minimize the risks by recognizing the threats and controlling as many factors as we can.” Crop diversification is a built-in strategy and the Bruns plant a wide variety of crops suited to diverse climatic conditions. An unseasonably cold, wet summer may be bad for some crops like tomatoes and peppers, but it’s good for others.

Hermann and Louise also made the business decision not to produce seeds. “We save one or two varieties of seed,” Hermann said, “but seed saving is almost another business. I think it’s a distraction.

The Bruns always seem to be experimenting with new ideas and the farm and its distribution system are constantly evolving. They once experimented with raising bees but stopped after the bees swarmed and migrated – better to leave bee raising to the specialists, Hermann said. On the other hand their egg production has grown considerably in the last few years; five years ago they had just a few laying hens and today they have around 100 that produce certified organic eggs.

Some of these experiments will be described in our next article, Bridging the seasons II: Timing is everything.

This is the first article in a three-part series on the popular Wild Flight Farm that sells fresh, organic produce at the markets in Revelstoke. For more information on Wild Flight Farm and to subscribe to their e-newsletter, click here.