By David F. Rooney

All week Parks Canada staff have been feverishly trying to save the history of our two local national parks from the effects of their sudden drowning last Monday night and their potential destruction by mildew and other fungi. It’s a race against time the ultimate outcome is still in question.

“We’re the triage unit,” said Rick Reynolds, Parks’ visitor services manager, as he and photographer Rob Buchanan examined cold, wet photos, slides and other documents pulled from a pool of cold water on Friday. “We’re not going to save everything. We’re almost out of time.”

The pool in question is an orange canvas pool filled with water, documents and images. They are being kept wet and cold at a salvage operation in one of Parks’ buildings on Mount Revelstoke because the low temperature water buys them precious time.

“It’s a lot of history,” said Buchanan who was drafted into the recovery effort as soon as he arrived back in town this week from a vacation in Turkey. “And some of it is irreplaceable.”

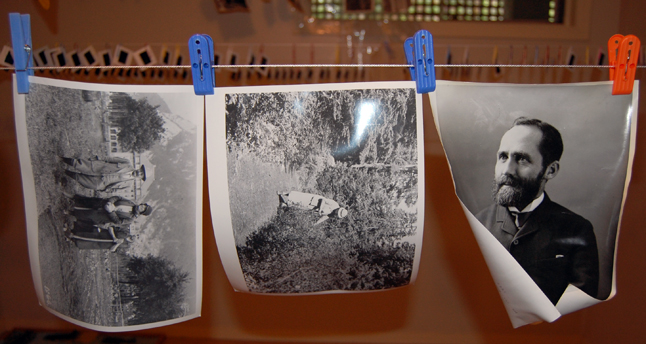

Among the documents that can’t be replaced are photos from the 19th century, original photos taken at the scene of the 1910 avalanche that killed 58 workers in Rogers Pass, hand-drawn maps and hand-written journals from the days when the Trans-Canada Highway was pushed through Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks.

“We’ve even recovered the original maps made of Nakimu Caves after they were discovered in 1906,” Reynolds said. “There are literally thousands and thousands of documents here.”

All of those documents, maps and images were in the Parks Canada Archive that occupied a large part of the basement of the building housing the Parks offices and the Post Office. At least that’s where they were when a water main broke and filled the cavernous basement with seven feet of water.

While the news media were not permitted to enter the disaster area one Parks staff member who saw it after the water was pumped out described it as “an unholy mess.”

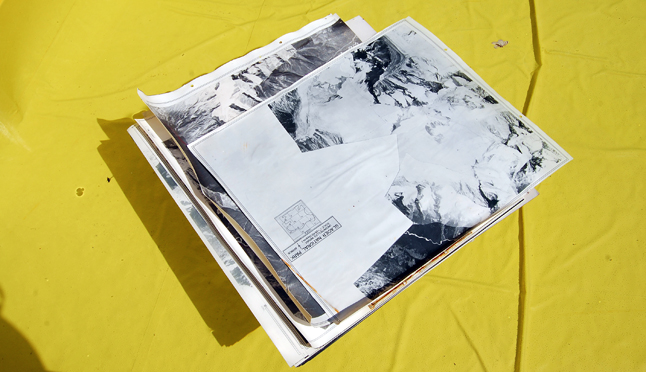

In the days since, staff have tried to save everything they could. Two conservators, Liz Croome and Jose Milne, were flown to Revelstoke on two hours notice from the agency’s Western and Northern Services Centre in Winnipeg to over see the salvage operation. Under their direction many materials such as paper records have been shipped up to the Parks compound in Rogers Pass and ensconced in a large walk-in freezer. They’ll later be sent off to be freeze-dried.

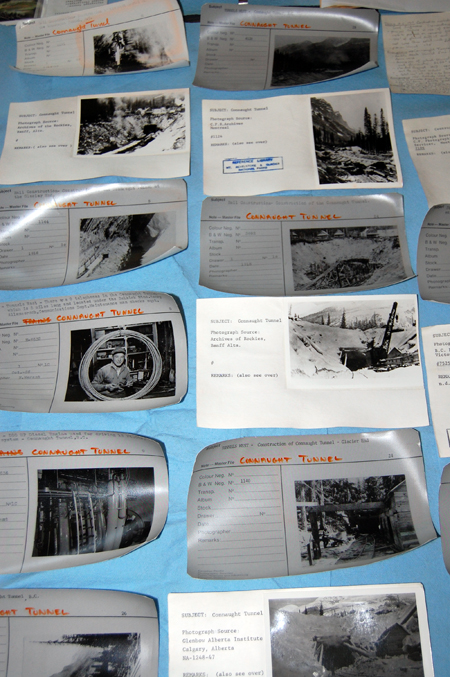

Thousands and thousands of other documents and images were taken to a Parks building on Mount Revelstoke where they were kept immersed in cold water until they could be individual examined, their value judged and then either dried and saved or discarded.

“Forty-eight hours is how much time the book says you have to save things after this kind of event,” Croome said as she guided me through the building. “We’re at what? Seventy-two hours? The cold water has bought us some time, particularly with the photographs and other images. If it was warm water their emulsions would have collapsed and they’d be irretrievably lost.”

Some other things such as animal pelts that formed part of the natural collection in the archive may well be lost.

“As you probably know, Parks doesn’t go out and kill and collect animals,” Milne said as we passed collections of rodents, martins and other mammals. Many of these were road kill before we got them so they were pretty rough. But they may be okay. The birds, however, don’t do well when they’re wet.”

Croome and Milne have helped organize the triage effort but they recognize that the real effort is being done by local staff — people like Reynolds, Buchanan, Lise Tataryn, Tania Peters, Tina Whitman and Marie-Claude Asselin who are all dressed in sweaters and whose fingers are looking a little blue from the cold.

“We’ve got the easy job,” Croome said. “We do the triage. For the people who live here this is a really long-term job. They’ll be dealing with the effects of this for years.”

And no one yet knows what the cost of the salvage operation will be, let alone the repairs to the building, said Parks spokeswoman Marnie Digiandomenico.

Here are images from the flood and the document-recovery operation: