By David F. Rooney

The storm that created the conditions for the killer avalanche of March 4, 1910, was a monster but it wasn’t that unusual, says John Woods, author of Snow War — An illustrated history of Rogers Pass, Glacier National Park, BC.

It swept across the entire Pacific Northwest starting on Feb. 23, 1910, as “a train of three storms that struck the western portion of the continent,” the retired Parks Canada biologist said in an interview. Over the next 10 or 11 days the storms brought alternating periods of mild and cold weather “that would be familiar to anyone living in Revelstoke.”

“This cycle was felt in Revelstoke on the 24th with a maximum temperature of -8.3° and 27 cm of snow while up in the pass it was -20° and there were 38.1 cm of snow,” said Woods who has spent years researching avalanches in the Rogers Pass.”

By March 4 there was a high of 6.7° in Revelstoke and 13.7mm of rain. Up in Rogers Pass the temperature had risen to 3.9° cm and they had received 55.9 mm of snow.

“We’ve experienced that kind of pattern many times,” Woods said.

That’s true. But our 21st century understanding of avalanches and their causes is light years ahead of the state of avalanche awareness in 1910. In any event, there were scores of men at work in the pass trying to clear the Canadian Pacific Railway’s main line of the snow that had been swept across it in the course of a number of earlier avalanches. As Woods put it in Snow War:

“The night of March 4, 1910, began like most other nights for the men working in Rogers Pass. A crews was at the summit clearing a big slide that had come down Cheops Mountain on the west side of the pass and had blocked the tracks. A rotary snow plow had cut a path across the piled snow on the line and men were working in the cut shovelling snow and clearing away trees swept down by the avalanche. The events which followed were to change the course of history in Rogers Pass.

“A half-hour before midnight, some of the men outside the cut heard a deep rumbling, then timbers cracking. An unexpected avalanche swept down the mountain opposite the first slide. Trapped within their snow-walled towmb, most of the men never heard the slide approach. Fifty-eight died.”

Alerted by Roadmaster John Anderson, who had fortuitously trudged away form the site before the slide, rescuers began to organize in Revelstoke.

One of those rescuers was Don G. Scott Calder who later recounted his experience. Here’s what he had to say:

“In Revelstoke on this March evening the air was balmy and very spring-like. During the day there had been talk among the railway employees about the effect of the weather creating unwanted snow slides. Already in the Rogers Pass area crews were busy clearing out several slides which had already occurred. In all eighty or ninety C.P.R. workmen were at work. The weather in Revelstoke on that March evening was so mild that none of the students had bothered to wear overcoats.

“As Charles (Procunier, son of the Rev. C.A. Procunier, Rector of St. Peter’s Anglican Church ) and I talked about the success of the High School party and the marvelous springlike weather which we were enjoying all of the Steam Whistles in the C.P.R. shops and roundhouse started to sound simultaneously. At the same time the fire gong at the firehall on Mackenzie Avenue started to ring. Procunier and I both aged 16 and dressed in our party clothes hurried down to the firehall. Here we learned that several snowslide clearing crews, locomotives, snow plows, etc., had been caught in a huge slide off Avalanche Mountain in the Rogers Pass area. Volunteers were being recruited to help dig out the entrapped men and like about 150 others mostly C.P.R. personnel we accepted shovels and walked with the rest of the rescue team down to the station where a special train awaited to take us up to the slide. No thought was given by either Procunier or myself of the fact that we were dressed in light party clothes. We were out on our first adventure mingling with adults. Not a few of the other volunteers were as lightly clad as we were ourselves. I am not certain of the exact number of volunteers assembled but an indication of the numbers is shown in a group of pictures of the slide area now shown in the Revelstoke Museum, well over 100…

“Proud in the fact that we were now part of the rescue gang we trudged with the rest of the volunteers through loose snow until we reached the

slide area. Here we met a devastating sight for the snow mixed with pieces of timber, shredded like matchwood was packed almost as hard as solid ice. Heavy picks rather than shovels would be needed and were quickly supplied. The whole side of the Mountain had been swept clear of timber, no signs of snowsheds anywhere. The snow from high above had formed a huge mass at which our railway guides and supervisors told us that they hoped to find the bodies of their comrades. It would be a miracle if any of them were alive. Charles and I looking into the stern faces of these men trained in the hazardous work in the mountain sections of the railway prepared for what we knew was to be perhaps our first brush with death. There would be no further slides in this area for the mountain granite stood out crystal clear.”

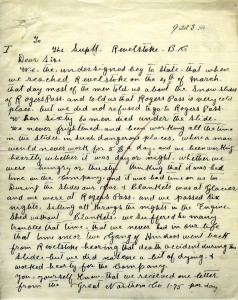

It’s easy to imagine that all of these men — Revelstoke volunteers and CPR crews — would be united in their efforts to retrieve the dead. If you think that, you’re wrong. A letter from one Mehar Singh (see below) details his complaint to the company about “abuse” he and his East Indian work crew suffered at the hands of white workers. It’s an ugly aspect aspect of an already terrible situation but it cannot be ignored. (Click on the images to see a full-scale version of the letter.)

There were survivors, of course. (You can read one newspaper account of a survivor’s story here.) And there were repercussions. The CPR spent three years digging the Connaught Tunnel, which opened in 1916. The line over the pass was abandoned.