By David F. Rooney

Read through the files and papers Museum Curator Cathy English has collected on the Rogers Pass avalanche and you can hear almost hear the quiet lamentation of the families of the dead.

Anne Moffatt of Belfast, Northern Ireland, writes to the Canadian Pacific Railway hoping for some kind of compensation as her dead son, James Moffatt, was his parents’ sole support.

“He went out to that country to help to support his parents but all won;t bring me back my dear son,” she wrote.

You can sensel her bewilderment as she is not even certain if she can recover any of his personal effects.

Another letter, from a man in Wales, thanks the CPR for sending his brother’s remains “for burial in our native place.”

And then there are the replies from the CPR to families and lawyers. Many are dry but elements of remarkable sensitivity and compassion do shine through.

“Harold, who has been with us for some time… was with a large nbumber of men clearing a snow slide on the railway line when another one came down and buried 58 men… some of the finest fellows we had here and your son was not an exception,” Supt. T. Kilpatrick wrote to the Martin family of London. “There was not a mark or scratch on Harold when we recovered his remains a few days later and he looked as natural as when alive.

“His remains were laid to rest in the Cemetery here yesterday, the English Church Minister holding services in Oddfellows Hall and at the grave.

“From what I can learn from those for whom Harold worked he was an exemplary young man and worthy of his Mother who writes him as you did. I am returning his Bible, a few letters and a photo of him taken at the steam shovel and shall write you later about any money or effects he may have left.”

The letters tell us little about the men who died, other than the fact that their families were, in a very stiff-upper-lip Victorian way, bereft. (Click here to read brief profiles of the men who died.) But we do know they were loved. We don’t know much more about the Japanese workers who died in the avalanche. These men were brought over by the Canada Nippon Supply Company as contract labourers. Their bodies were all recovered and they were buried in Vancouver.

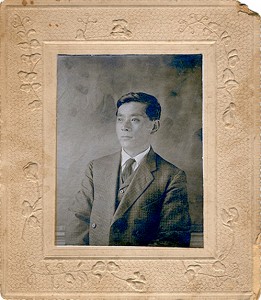

The Canada Nippon Supply Company no longer exists and none of its records are available so we have little information in this country about how the families of those workers reacted to the death of their loved ones. It’s hard to imagine that their grief would be any less than that felt by the European families. The museum does have images from one of the Japanese workers’ funerals — that of Bookman Abe Masatora.

Tomo Fukimura of Revelstoke has been researching the background of Japanese workers killed in the 1910 avalanche and has tracked down several of their relatives. Three of them will be here for Thursday evening’s commemorative service (click here to read the official Commemorative Service program) at Grizzly Plaza and others will be here for commemorative services planned for Rogers Pass in August.

Copies of some of the letters, which are housed at the Revelstoke Museum & Archives, are reproduced below. Please click on the images to see larger versions.